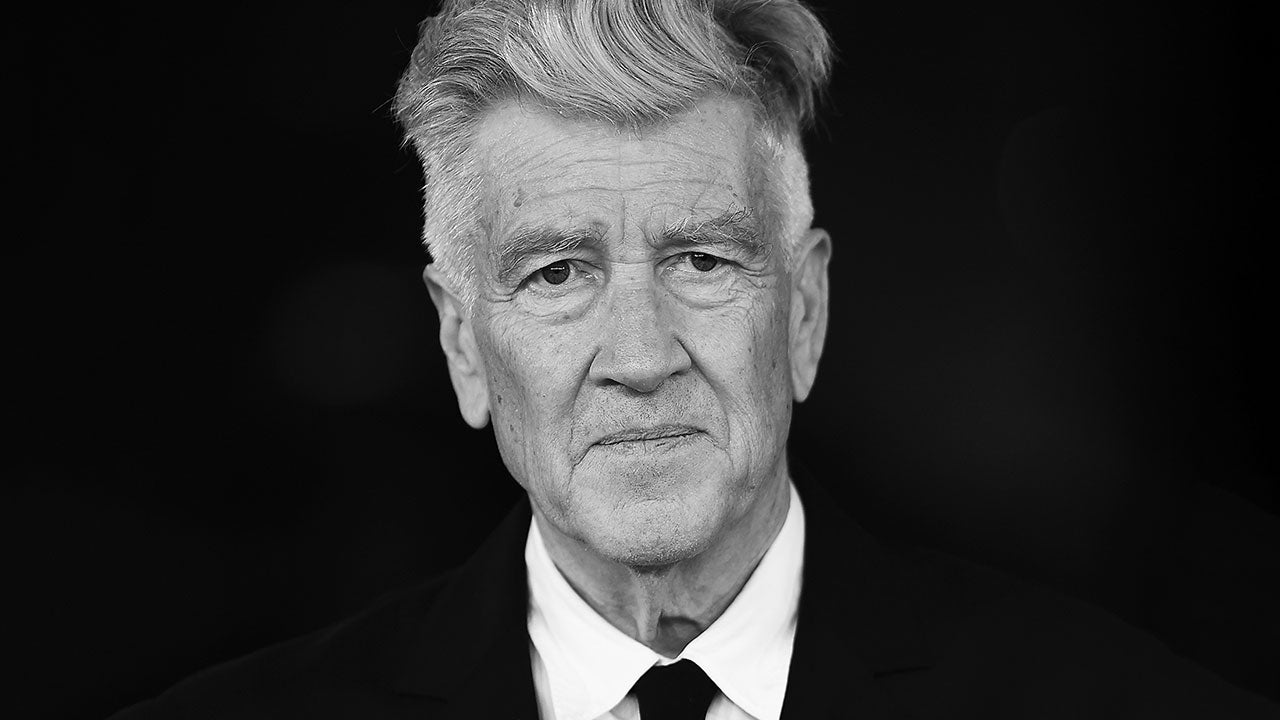

There’s a scene in the Twin Peaks pilot that starts with the normal, humdrum, boring rhythms of everyday life. We’re in a high school, where a schoolgirl sneaks a smoke, a boy is called to the principal’s office, attendance is being taken in a classroom. But then a police officer steps into the class and whispers to the teacher. Suddenly, a scream is heard, and outside the window a student can be seen running across the courtyard. The teacher is holding back tears. There’s going to be an announcement. And then David Lynch trains his camera on the empty seat in the middle of the class, as two students look at each other across the room and realize all at once that their friend Laura Palmer is dead.

Lynch was always good about recording the surface-level details of life, but it’s because he couldn’t help but pick apart those details in his work – according to Lynch, always, just always, there was something lurking beneath the surface that was just not right.

In many ways, that Twin Peaks moment is the definitive David Lynch scene because of how simply and subtly it establishes the thematic throughline of his career. But then again, it’s also very much not the definitive David Lynch scene because he had so many moments his fans could point to over the span of his 40-plus years of making movies, TV, and art. Ask any coffee-drinking, weather-report-watching, card-carrying Lynch fan and you’ll likely get a completely different response on the matter.

And this is the heart of what is one of the most difficult things to accept about his passing for us fans. Here was an artist who had such a singular voice, but whose appeal lies in different places for everybody.

There are few who can claim to be deserving of a brand-new adjective. Everybody has their style, their trademarks, and there is no shortage of films that have been described as “Spielbergian” or “Scorsese-ish,” but that misses the point. Those always describe something specific in the lighting, for instance, or subject matter. But then there’s “Kafkaesque,” which can be applied to damn near anything that’s just really unpleasant and disorienting. It’s a bigger term than the specifics of the work that coined it, and it is to this exclusive club that “Lynchian” belongs.

When you can’t quite put your finger on what’s amiss, it may as well be Lynchian. It’s that unnerving, dream-like quality that made David Lynch a legend, and his status as such isn’t likely to change.

Watching Lynch’s midnight movie classic Eraserhead was something of a rite of passage back when we were a budding film nerds, though little did one of us know that decades later his teenage son would be undertaking that same rite (with Dad right alongside him). But it wasn’t just because I (Scott) was telling the kid that he had to watch Lynch’s stuff. No, one day the kid and his girlfriend just started binging Twin Peaks by their own accord. (They were in the Windom Earle era of Season 2 at this point, God bless.)

There’s just always been something about the guy’s work that has made it timeless in an odd sort of way – with odd perhaps being the applicable term. How else can one explain how when Twin Peaks: The Return finally happened in 2017, Lynch chose to give the little kid in the show a bedroom that looked like it belonged to a 10-year-old from 1956 with its cowboy trimmings and all? (Lynch, perhaps not coincidentally, would’ve been 10 in 1956.) Of course, that kid in The Return also happens to live in a really fucked-up world that only David Lynch could dream up, one where his father is some kind of clone from another dimension and where there’s another, evil clone as well who practically punches his fist through a guy’s face at one point.

The Return came at the height of the “let’s greenlight every nostalgia play” we can think of boom in Hollywood, but Lynch of course took that greenlight and then did whatever he wanted with it. That included leaving the audience as high and dry as any in TV history by refusing to bring back the original Twin Peaks’ most important characters in any meaningful way. And why should he have? That would’ve been the most un-Lynchian thing he could’ve done.

Look at what happened when Lynch did play by the rules of the more conventional Hollywood game. His Dune is one of the most infamous misfires of the past half-century, but it’s also very specifically a David Lynch movie even when it was an Alan Smithee movie. The filmmaker was famously troubled by his experience making Dune – a topic you can explore fully in our friend Max Evry’s book, A Masterpiece in Disarray. And while the legend of Paul Atreides and the Fremen and the Harkonnens and all the rest of it is there in Lynch’s version, it’s all peppered with imagery that could’ve only come from the guy who a few years earlier gave us the most nauseating chicken dinner ever put on celluloid. I mean, who comes up with a cat/rat milking machine other than David Lynch? You can almost hear him now: “It’s the future, folks!”

But there’s a beauty in Lynch’s imagery as well, however weird or funny or disturbing or anachronistic it is. His second feature, The Elephant Man, is as close to Oscar bait as the guy ever came, but it’s also an extremely touching and lovely film that happens to be set in an extremely disquieting time and place in history, a world where sideshow freaks actually existed, where their mistreatment was very real and where a gentle soul like John Merrick didn’t have a chance in the world. Until he did.

That’s fucking Lynchian too, guys.

Defining his work, pinning it down to genre or trope or any of those other boxes we try to use is a fruitless effort, but dammit if it isn’t easy to pick a David Lynch movie out of a lineup. That was his magic. His film and TV work was dark and funny and dreamlike and surreal and very genuinely strange but in an organic way and a million other things that his admirers will be sure to highlight in the coming weeks, like we’re doing right now. One of our favorite things about his films is that he was obsessed with a world beneath the one we live in and pulling back the (sometimes quite literal) curtain to reveal what’s lurking behind it.

Take Blue Velvet, for instance. On one level it’s a pretty standard noir following an everyman becoming something of an amateur detective to follow clues and put away the bad guy. The setting is a Norman Rockwell painting, full of white picket fences and girls-next-door, but Kyle MacLachlan’s Jeffrey descends past that facade into the world of gas-huffing drug dealers and loungey lip-syncers that is anything but “standard.” Rooted in the veneer of a mid-century Americana that’s plainly depicted as being “not the whole truth” at minimum, all of Lynch’s work was tinged with a healthy dose of surrealism and wholly unconcerned with being grounded. There’s a great documentary digging into Lynch’s relationship with The Wizard of Oz which follows that particular yellow brick road even further, but the point is the influences at work in his films, Blue Velvet included, are a set that simply doesn’t exist anymore, and we’re not likely to see again.

At this point in movie history, we’re effectively on our second or third generation of filmmakers inspired by the previous generations. In the beginning of cinema as an art form there were artists from other disciplines using film as their chosen medium. As more of the road stretched out behind us, so to speak, filmmakers wanted to make movies like the ones they grew up watching. Lynch of course is among those.

But for as unique an artist as he was, at some point he stopped being a distinct collection of influences, and became the influence himself, and that is where we come back to the term “Lynchian” and why we’re likely to just never see the like of him again.

There’s a moment in the middle of one of 2024’s more unexpected hits, I Saw The TV Glow, where the protagonists find themselves at a bar listening to live music. The way the camera floats, the theatrical wardrobe of the singer, the red, strobing lights out of time with the cadence of the song – it’s there to create an atmosphere and it’s as Lynchian a scene as we’ve gotten in some time. Jane Schoenbrun’s film trades in the type of surrealism familiar to Lynch fans and was in fact inspired by Twin Peaks. One of the great things about a rangey term like “Lynchian” is that you can see his influence across a wide array of films and filmmakers.

Yorgos Lanthimos has a darkly comedic sensibility that peels back layers of polite society. Think about The Lobster, and how it pulls people out of the real world, sequestering them in a hotel where they have to find love or risk being turned into an animal. It’s the absurd scrutiny of the everyday things we take for granted that reveals that Lynchian thing lurking under the surface. Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse is an avant garde bit of nightmare, ditto Ari Aster’s Midsommar. We’ve gotten David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows and Under the Silver Lake, and Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn. There’s Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko and another standout 2024 hit, Love Lies Bleeding from Rose Glass. Lynch is clearly on Tarantino’s list of filmmakers to homage, and there’s even fellow Dune director Denis Villeneuve’s pre-blockbuster stuff like Enemy or Maelstrom which have an otherworldly quality to them that owes a debt to David Lynch.

David Lynch might not be your favorite filmmaker, and maybe you haven’t seen all of his films or they’re just not your thing, but it’s important to recognize him as something of an end of an era. Like his films that invoke a bygone time only to explore the world just beyond our usual frame of view, his influence on today's and tomorrow's filmmakers is what he leaves behind. We, for one, will always be looking just under the surface hoping to find those “Lynchian” things lurking.

Header photo by Stefania D'Alessandro/Getty Images