Capcom’s Devil May Cry returned to the small screen earlier this month with a new animated adaptation from creator Adi Shankar and animation house Studio Mir. The show appears to be a success; Devil May Cry is the fourth-most-watched series on Netflix right now, with more than 5 million views, which feels pretty impressive for a game franchise that hasn’t had a new entry since 2019. Netflix recently announced a second season of Devil May Cry.

Shankar’s Devil May Cry anime has been a long time coming. First announced in 2018 as part of Shankar’s “bootleg universe,” the showrunner has clearly poured years of effort and enthusiasm for Devil May Cry into his show. The series is “1/4 a love letter to Capcom and 3/4 a DMC show,” Shankar says, with nods to Resident Evil, Captain Commando, and the demon worlds that span multiple Capcom franchises, like Onimusha, Cyberbots, and Ghosts ’n Goblins.

Devil May Cry is also deeply personal to Shankar. He has, after all, very publicly cosplayed as series protagonist Dante. But beyond the love of the game and the character, the new Devil May Cry series is representative of a time in Shankar’s own life. He was a fan from the series’ inception in the early aughts, and like other Devil May Cry fans, experienced the franchise’s ups and downs, which influenced his creative process.

Polygon recently caught up with Shankar to talk about his connection to Devil May Cry and how it’s influenced his own tastes. You can read our conversation, conducted via email, in the Q&A below.

Polygon: Can you recount the Dino Crisis-to-Devil May Cry meeting with Capcom that you had?

Adi Shankar: I went into the very serious business meeting with the intention of getting Dino Crisis, but I was dressed like a DMC character… so after I told Capcom executives I wanted to bring back Dino Crisis, they suggested I should do DMC.

How would you describe your relationship with the Devil May Cry franchise? When and how were you introduced to it?

I played the first game right when it launched in 2001. I was sixteen, I had just moved away from home to America, and two days later, 9/11 happened. That moment — that feeling of the world shifting overnight — would go on to shape everything for me. Weeks later I went into Devil May Cry blind, knowing only that it came from the creators of Resident Evil. Naturally, I expected fear. I expected the kind of survival horror dread that defined RE2. But what I discovered instead was this awesome shift: Resident Evil made you feel like prey, Devil May Cry made you feel like the hunter. That power fantasy hooked me immediately.

From there, I followed the franchise through all its incarnations. And I’ll be honest — when DMC3 first dropped, I was skeptical. Dante felt too irreverent, too flamboyant at first. But over time, I came to understand that this wasn’t excess for its own sake — it was a deliberate stylistic choice that revealed new layers of the character. The same thing happened with Nero in DMC4. I initially resisted him, thinking Capcom was grooming a replacement for Dante. But DMC5 brought it all together in a way that felt inevitable. It showed me that evolution and loyalty to the franchise can coexist — that progression doesn’t have to mean erasure.

I was a part of the backlash to DmC: Devil May Cry. I viscerally experienced the fear of losing what made the series special. But with time and distance, I can appreciate that even that chapter kept the Devil May Cry fire alive. It forced the community to articulate what we loved about the series. It kept the conversation burning. Because the death of any franchise isn’t risk — it’s apathy.

Being a Devil May Cry fan never felt like the obvious choice. It wasn’t the safe, mainstream pick. It didn’t have the cultural ubiquity of Street Fighter or Resident Evil. It was something for those of us who wanted to live a little bolder. There’s a certain pleasure in choosing the thing that feels slightly dangerous, slightly transgressive. That, to me, is the visual essence of Devil May Cry: It’s style executed with discipline.

And as I got older, I started to understand something deeper about my connection to DMC. A lot of us who found DMC early were carrying something heavy. Loss, grief, the invisible weight that shapes you before you even have words for it. What I came to recognize is that Devil May Cry doesn’t ask you to hide that pain. It invites you to confront it directly and sharpen it into something formidable. Pain becomes strength. Grief becomes drive. The darkness isn’t something to escape — it’s something to master. There’s an emotional honesty to that, which has always resonated with me.

My relationship with Devil May Cry is the same relationship I have with any brand I believe in deeply. I become obsessed with understanding the architecture behind it — the logic, the fine details, the invisible forces that make it feel alive. I don’t just consume it; I deconstruct it. Because if you’re going to carry the torch for something this meaningful, you owe it that level of respect and rigor.

You’ve cosplayed as Dante — what about the character resonated for you?

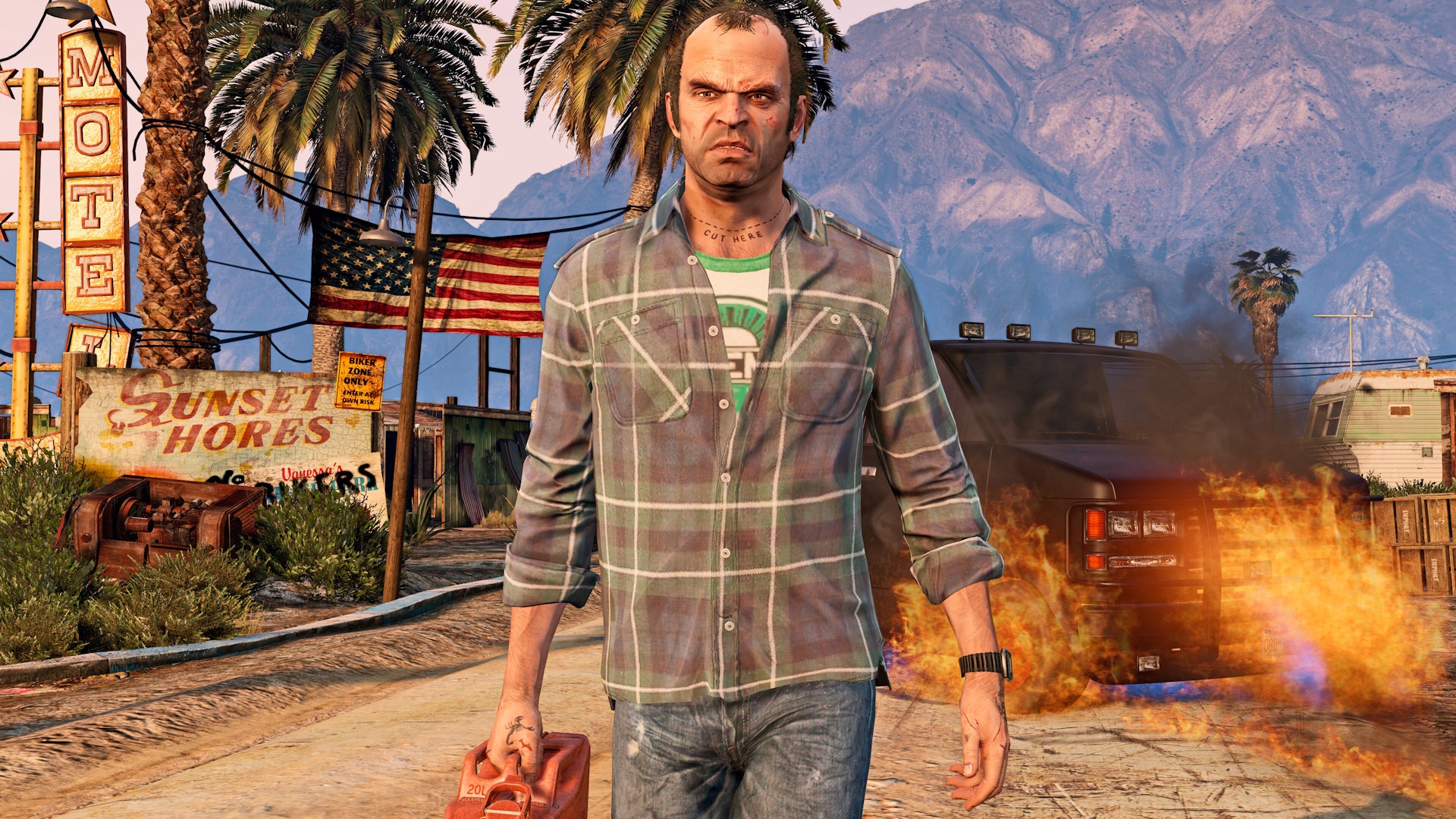

For me visually, Dante represents the apex of what video game character design is capable of — and, frankly, a benchmark the industry needs to remember as we evolve. He’s not just cool, he’s engineered cool. Instantly iconic. Instantly legible. We talk so much in the games industry about immersion and photorealism, but sometimes that pursuit sacrifices character silhouette and visual identity. Dante slashes through all of that noise.

When you think about Pac-Man, Sonic, Mario, Duke Nukem, M. Bison — these characters were crafted to be cultural touchstones. Dante belongs in that same pantheon. His design is franchise-defining. It gives you a visual language that communicates everything about the game’s tone and energy before you even press start.

In my view, the industry at large needs to re-embrace this level of iconic design. What’s interesting to me is that, as the industry has pushed towards photorealism, I feel like we’ve lost some of that bold, exaggerated character design. Realism has its place, of course, but it can sometimes dilute the immediacy of an icon.

How much of yourself did you put into Devil May Cry?

I put all of myself into this. I created the story, the framework, the entire architecture of this DMC universe on Netflix. So in that sense, every frame is me with the major help of Alex Larsen. But it’s not autobiographical. My process is about merging with each character, no matter who they are, to understand them. Great art is the pursuit of truth. I have to find empathy for everyone, because in my view, every character is the hero of their own story. Even the villains. Especially the villains.

Take Baines, for example. Some fans have reacted like he’s anti-Christian, like I was taking shots at Christianity with his character. And to be fair: Christians absolutely have reason to feel like they’re being dunked on in the media — a lot of times they are. I’ve only met wonderful and kind Christians in my life and I have no issue with Christianity. I went to mostly Christian schools and I studied Christianity in school. If you look at Baines objectively, he’s not a villain. He’s a man trying to save his country, his world, from literal Armageddon. And here’s the thing: He was right. Hell exists. The genocidal, demon-powered rabbit was real and is trying to bring hell to Earth. And no one else was taking that threat seriously. Without Baines, the world would’ve fallen in five minutes flat. #BainesWasRight.

That’s the kind of depth I work to bring to every character. Even a C-level villain like Plasma — who in the games is a fairly traditional copycat henchman villain — I gave him his own ideology, his own internal logic, his own reason for existing in this universe; his arc tragically culminates in [season 1, episode 5] (he may or may not be dead). Because to me, that’s the storyteller’s real responsibility. It’s not enough to just create cool fights or slick visuals. You have to breathe life into every corner of the world. You have to build it so that every character feels like they could lead their own spinoff story, like they could step into the spotlight at any moment.

Netflix’s DMC was a long time coming, as you mentioned in your Geeked Week video in 2023. What was that extended process like for you? What was most important for you to get right?

Given the state of the games industry, and the wider economic landscape, if my Devil May Cry series had been canceled after one season, it wouldn’t have just been a setback for the show — it could have seriously damaged DMC as an IP. It’s a tough truth, but that’s the reality of how these decisions are now made at the corporate level. The more attention and success my DMC series commands, the more confidence the industry has to invest in the DMC franchise. And, more importantly, the more the franchise grows, the more backing visionary, generational talents like Hideki Kamiya and [Hideaki] Itsuno-san will receive to continue making their new games.

In 2025 growth is a business imperative and essential for survival. If DMC is going to survive and thrive long-term, it needs to reach new audiences. For me, the best way to honor Kamiya-san and Itsuno-san isn’t simply to preserve what they built — it’s to expand it. It’s to create new opportunities for their visions to flourish, to make sure that what they poured their life energy into doesn’t just endure, but evolves and thrives in the future.

So I approached this as an original universe, much like Marvel’s Ultimate Universe or the series X-Men Evolution: a universe that honors the legacy, and eventually arrives at many of the same story beats (albeit through different paths). This is a new universe. A new continuity. It’s not a remake but it’s a retelling.

One of the most important things for me was fleshing out parts of the mythology that were only ever hinted at in the games. Take Makai, for example — it’s a major element in Devil May Cry, but it’s always felt like a distant, shadowy concept. Yet, what fascinated me is that Makai isn’t just isolated to DMC. It’s part of a larger Capcom cosmology. You see Makai in Darkstalkers, Cyberbots, even as thematic DNA in Onimusha and Red Earth. And beyond Capcom, Makai draws directly from Japanese mythology — the demon realm, the underworld, a place of chaos and power. I wanted to explore that fully and weave it into the narrative fabric of this series.

The way I saw it, Season 1 had to be the gateway drug — the on-ramp for both newcomers and casual fans. But with the introduction of Vergil in Season 2, the storytelling pivots and that’s when I start speaking more directly to the hardcore fanbase, the purists. Season 2 is where we honor the legacy at full tilt. So it’s all been designed like a long game — an architectural plan to build and expand the entire Devil May Cry universe across seasons.

The first season is just the first chapter of an epic saga.

What are you hoping that Devil May Cry fans understand about the series and your approach to it?

What I hope Devil May Cry fans understand is that the best way to grow an IP is to have multiple creators take extended runs with it. That’s actually part of why DMC has endured for over two decades. Hideki Kamiya created it in 2001, and then Itsuno-san came in and made it his own with DMC 3 (2005), 4 (2008), and 5 (2019). Each brought their own vision and passion to the universe, and that’s what keeps a franchise alive — when it passes through new hands, as long as those hands love it.

Even the Ninja Theory reimagining in 2013, which got plenty of criticism at the time, ultimately helped DMC. It kept the franchise in the conversation, expanded its reach, and tested creative boundaries. That matters. Because what kills a franchise isn’t experimentation — it’s stagnation. DmC sparked debate, sure, but it also proved that the appetite for Devil May Cry was still strong, which helped pave the way for DMC 5 to become a global hit years later.

If you look at the most enduring brands in the world — Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, Gundam, Game of Thrones — they’ve all thrived because of creative reinvention. Frank Miller redefined Batman in 1986 with The Dark Knight Returns, giving the character a darker, more psychologically complex edge that shaped decades of storytelling. Clint Eastwood’s portrayal of the Man with No Name took the American Western, which was on the decline, and redefined it through the lens of the spaghetti western — giving it grit, style, and global appeal. Todd McFarlane brought an entirely new visual dynamism to Spider-Man in the late ’80s and early ’90s, making him feel young, kinetic, and more alive than ever. Benioff and Weiss took Game of Thrones, which at the time was a fairly niche fantasy novel series, and turned it into one of the most globally recognized brands on Earth. And last year Beau DeMayo did something remarkable with X-Men ’97 — he took a beloved but dormant property and made it feel urgent.

Reinvention is the key to longevity. You have to respect the legacy, but you also have to push it forward. And — this is just my philosophy — if you’re stepping into the driver’s seat of a franchise like Devil May Cry, you have to come in with a 10-year plan. That doesn’t mean you won’t pivot along the way, or even that you’ll get the opportunity to fulfill the entire 10-year plan, but you must begin with that level of vision and commitment. If you don’t, you’re setting yourself up for failure from day one.

Source:https://www.polygon.com/tv/558731/devil-may-cry-anime-netflix-adi-shankar-interview