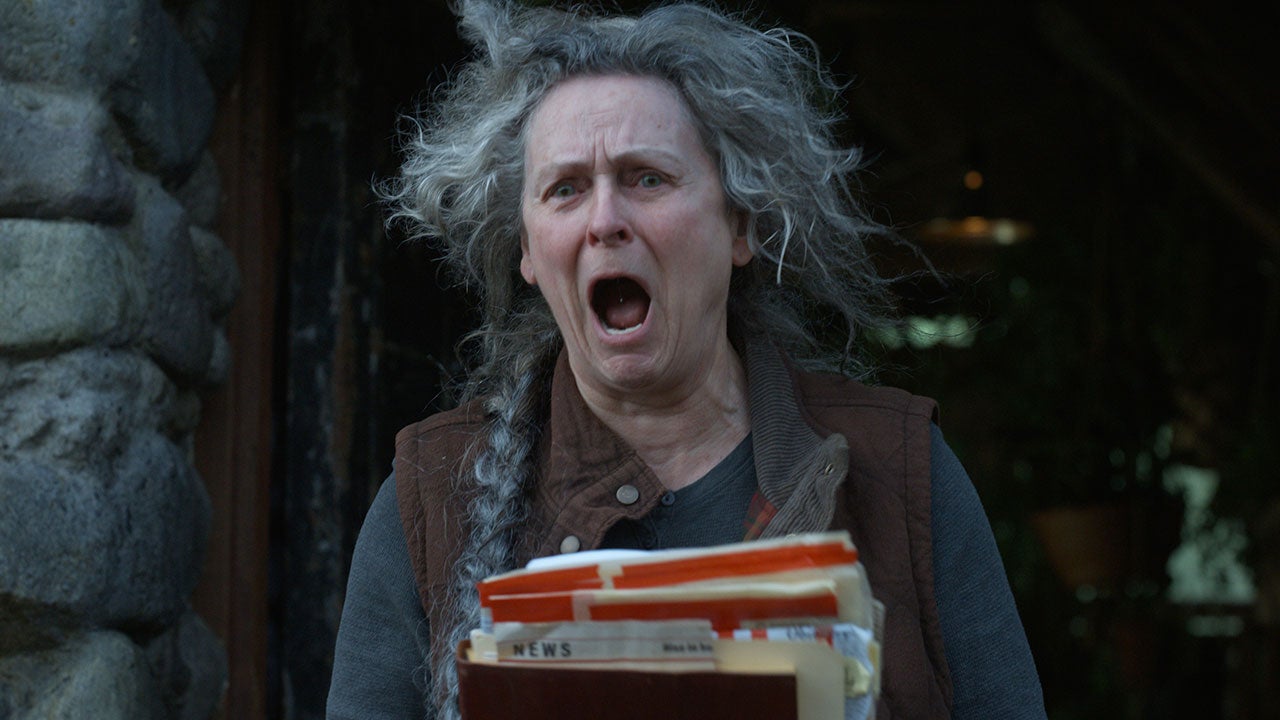

The first time sticky notes almost killed me in Remedy Entertainment’s FBC: Firebreak, the new multiplayer spinoff of 2019’s Control, I laughed out loud. A slow death brought on by the overwhelming horde of memos you’re tasked with destroying is the most fitting demise in a game that leans heavily into satirizing corporate life.

The fourth sticky note death elicited a small grin and more than a little annoyance, as the Post-Its gradually obscured my vision and consumed my soul mere seconds before I reached safety. The 10th barely registered; saving myself from note death was just another task to deal with so I could get back to ticking off other tasks that had become just as rote, collect my meager rewards, and do it all again, all to inch slowly toward unlocking a new perk or upgrade. That’s FBC: Firebreak in microcosm, a collection of strong, inventive, and initially enjoyable ideas that strains and breaks when stretched over a live-service frame.

In Firebreak, a supervisor in The Oldest House sends groups of nameless cleaners into the building’s depths to deal with the Hiss — Control‘s enemies from another dimension — and other problems. The mid-century architecture of Control is present, and Firebreak turns the jibes about corporate drudgeries and petty managers from Control into its entire ethos. Little else makes it recognizable as a Control game, though, and it makes no effort to tell a new story or any story, for that matter. The focus is entirely on the job.

Each job sends you into The Oldest House to deal with hordes of Hiss and fix a specific problem, ranging from blowing up pink goop that’s smothering generators, to blowing up piles of sticky notes before they consume your soul and harvesting irradiated pearls from giant leeches. Shower stalls cure every status ailment, washing away sticky notes, fire, and radiation alike, and cleaners quip about their desk jobs and the Bureau’s sketchy history. It’s ridiculous in the best ways and quite fun if you’re playing in a group — at least, initially.

A good live-service game knows how to keep things interesting over a long period of time, either by doling out meaningful upgrades at a fixed pace, letting you unlock new modes or objectives, or doing something that creates a sense of progression and encourages you to play again. Firebreak tells you everything about itself upfront and then remains unchanging. That static concept works in a single-player game, but not in a format that demands evolution. It feels like Remedy relied on the worst tendencies of live-service games — grinding and the expectation that because you can unlock something, you’ll want to — instead of creating unique ways to approach the formula.

Characters start with one of three job kits: a giant wrench you hit things with; a splash machine that blows giant water bubbles; or a jump tool that generates electrical charges. Each can make one part of a mission easier by letting you bypass a task, such as charging a generator or repairing a broken machine, and they all have secondary functions, at least in theory. The repair kit is meant to double as a melee weapon, though I didn’t notice any extra damage or staggering if I hit a Hiss with the wrench or used a standard melee attack. The splash kit removes negative effects and applies the wet status, while the jump kit electrifies enemies.

Handling a task without the right tool takes longer, with a quick-time event that has you press dozens of buttons in a process that seems designed to create artificial tension. You can recharge a battery instantly using the jump kit, but it takes about 10 seconds to do manually, putting you at risk of getting overwhelmed by Hiss swarms. The kits are inessential and seem like a compromise, where Remedy perhaps didn’t want to create the kind of rigid character roles common in multiplayer shooters, but also needed some kind of structure to encourage cooperation between players. Like most things in Firebreak, the novelty of each kit wears out after clearing a few jobs.

Firebreak launches with five jobs, each with several difficulty levels and additional locations in the House for you to clear. The actual jobs remain the same, though. The third stage of Hot Fix, the initial job, is the same as the first stage, only with you repairing furnace fans in three large areas instead of one or two. There’s little incentive to keep replaying despite that clearing the same mission over and over is the only way to earn loadout improvements.

Enemy variety was never Control’s strong point, and Firebreak has even fewer types of Hiss to plan around. There’s a standard, zombie-like Hiss that comprises roughly 80% of the enemies that spawn during a job, along with security guard-style enemies who use guns and a sturdier foe equipped with explosives. A small squad of airborne Hiss will occasionally spawn, though these are rare. The “powerful” enemies you have to defeat before the service elevator arrives to whisk you to safety are drawn from this pool. They behave the same as their standard counterparts, but with more health, until you challenge higher clearance levels and start encountering a handful of more bizarre creatures, like a humanoid monster comrpised of sticky notes.

A small layer of strategy, where enemy type and map layout force you to consider the best approach for a given situation, helps keep games such as Left 4 Dead from becoming stale even as you replay the same mission multiple times. You might take a stealthy approach and bypass a large group of enemies, use precision weapons to take out the strongest before the team moves in to deal with the rest, or rush in with grenade launchers blazing and try your luck. It isn’t deep, but there are enough variables that your choices influence how the mission plays out.

That decision-making just isn’t here in Firebreak, and even as you venture deeper into the House, the maps don’t lend themselves to more dangerous or strategic situations. It’s more of the same, with maybe an extra environmental hazard or two. Fires make Hiss stronger, but extinguishing blazes takes so long that you’re better off eliminating the Hiss and ignoring the flames entirely — ironic, given Firebreak’s name. The only difference your weapon choice makes is how quickly you reload, at least until you start unlocking a handful of improvements. That won’t happen for several hours, though, and getting to that point feels like a thankless chore, the kind of job you clock in for only because you have to.

Perks and upgrades are a mix of Remedy’s trademark quirkiness and the genre’s worst tendencies. Some of them are great, like the perk that makes you run faster when you’re on fire — amusing, but also useful for reaching safety more quickly. Most are typical of any shooter or action game, such as conserving stamina while sprinting or strengthening shields so they withstand more damage. They’re fine and useful, but nothing to get excited over. The prevalence of standard upgrades and comparative sparseness of improvements that have more of Remedy’s style or even Firebreak’s irreverent attitude is disappointing, but not as much as the method by which you acquire them.

All perks cost points that you earn by completing a mission, and you can get extra points for collecting research files. Even a successful mission where the team collects plenty of research files will typically only reward you with 10 points or so, which won’t get you far as you start trying to unlock higher-tier upgrades. However, you also have to increase your player rank, which takes even longer. Acquiring new weapons and other loadout upgrades, including better grenades, is part of another annoyingly tedious process. Firebreak has these in a separate menu, but you can’t access most of them until you clear an entire page of upgrades. That costs dozens of points — points you also need for new perks — which forces you to spend them on voice lines, sprays, new cosmetics, and other things you might not even want. It feels like a grind for the sake of it.

Firebreak has a good start point and some decently fun combat improvements at the end point, but the route between the two is shallow and poorly realized. The tasks in each job are too simple and basic to warrant the amount of time Firebreak wants you to spend replaying them. By the time you unlock those endgame combat improvements, it’s not enough to make repeating the tedium again an attractive prospect. In other words, there’s just not enough substance to warrant Firebreak as a live-service game.

Granted, since Firebreak is a live-service game, progression issues, lack of variety and creativity in upgrades, and all the other annoyances can and possibly will get ironed out over time. More ways to play and actual incentive to keep replaying would make a substantial difference, even if it doesn’t fully make up for the shallow, repetitive mission design. At launch, though, Firebreak: FBC is like any job task: best approached in short bursts so you don’t burn out quickly.

FBC: Firebreak is out June 17 for Windows PC, PlayStation 5, and Xbox Series X. The game was reviewed on Windows PC using a prerelease download code provided by Annapurna Interactive.

Source:https://www.polygon.com/review/607291/fbc-firebreak-pc-ps5-xbox