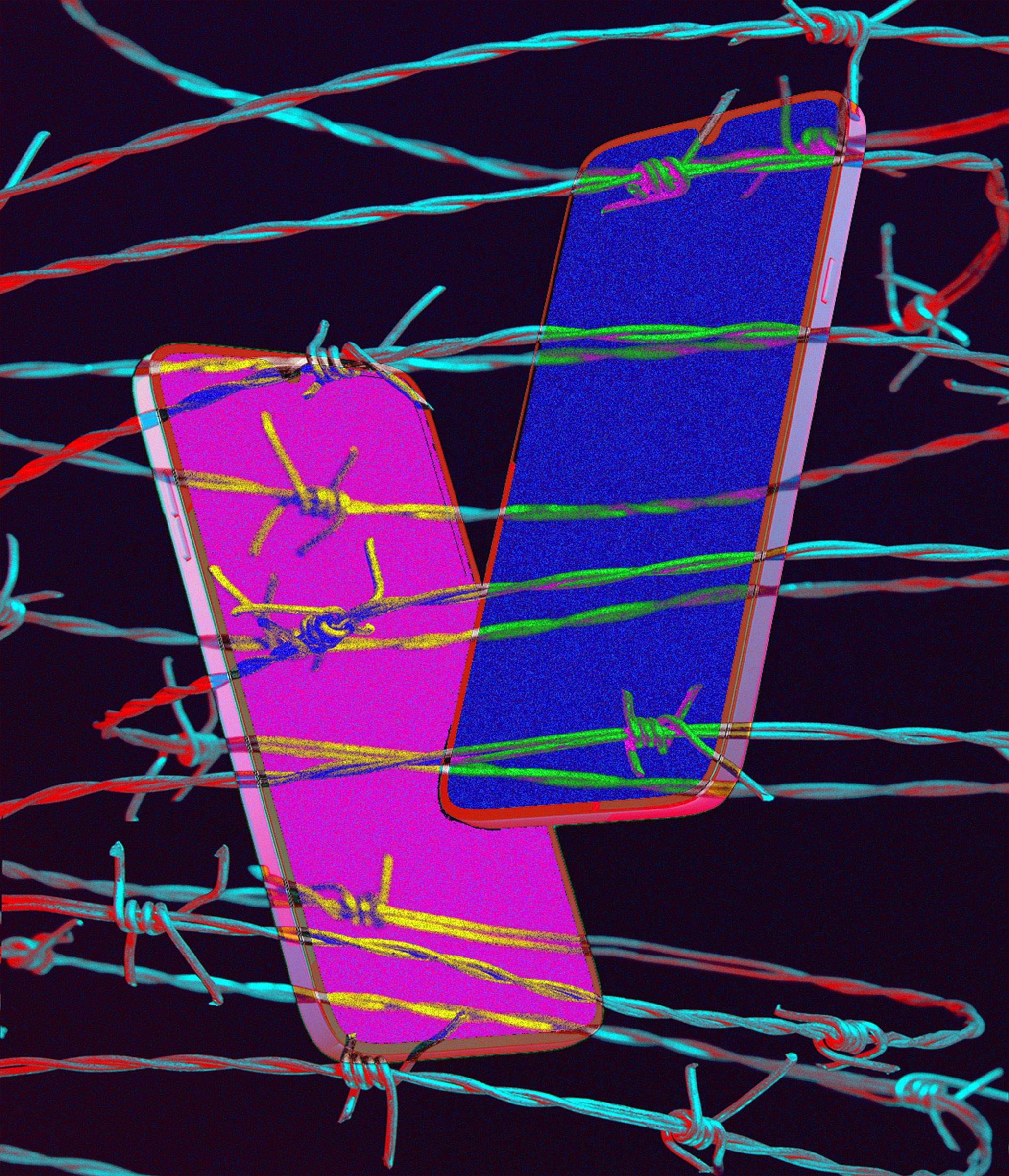

Season 2 of The Last of Us has faced considerable backlash for its divisive narrative swings and polarizing character arcs. But beyond the bad-faith criticism centered on queer representation or Bella Ramsey not looking enough like her game counterpart, there are deeper, more valid concerns about how the show steadily eroded its lead characters. A lot of the recent conversation has focused on a perceived drop in quality from season 1 to season 2, with viewer ratings for the second season plummeting.

But those accusations are missing the point. The issues fans are complaining about didn’t suddenly appear in season 2; they were already showing in the series’ initial season.

[Ed. note: Significant spoilers ahead for The Last of Us, the TV series and the games.]

Co-showrunner Craig Mazin has a habit of anchoring his stories around a singular narrative event, whether in his HBO series Chernobyl or (less seriously) his Hangover movies. In The Last of Us, that central event is the murder of post-apocalyptic survivor Joel (Pedro Pascal). Joel’s death is foreshadowed thematically throughout season 1, where characters like Henry (Lamar Johnson) and Marlene (Merle Dandridge) are positioned as tragic figures forced to sacrifice loved ones for the greater good before dying.

Their arc lays the groundwork for Joel’s similarly structured climactic decision about whether to sacrifice Ellie (Bella Ramsey) in the attempt to find a cure to the Cordyceps brain infection. When the Fireflies group attempts to dissect Ellie to investigate her immunity to the infection, Joel storms in with seconds to spare, gunning down the doctors in cold blood.

While his choice is in line with the games, the TV adaptation takes detours and different routes to get there. The show’s penchant for spelling out Joel’s conflict, combined with Neil Druckmann’s decision to reinsert cut content from the games to make the story more simplistic and morally palatable, ultimately flattens the ambiguity that made the original The Last of Us game so compelling. Rather than keeping the small moments that broaden the relationship between Joel and Ellie in the game, season 1’s focus on expanded backstories and doomed side characters who are meant to mirror Joel’s arc only dilutes it. The extra material left behind a version of the story that feels safer, less challenging, and far less impactful.

The first season of HBO’s The Last of Us paints Joel in a far more sympathetic light than the game ever did. From episode 1, Mazin, Druckmann, and their writers expand Joel’s relationship with his daughter Sarah (Nico Parker), giving audiences more time to connect with her and understand their bond. The emotional investment they establish for the audience is designed to make Sarah’s sudden death hit harder. But it also spells out everything Joel is thinking in his internal struggle over whether to protect Ellie, making it less ambiguous and more sentimental. While the added sequences with Sarah are affecting, they don’t contribute much to the season’s theme of loss and sacrifice, beyond softening Joel’s image.

Later in season 1, Joel begins having panic attacks after witnessing the deaths of young survivor Sam, who succumbs to the Cordyceps infection, and his older brother Henry, who shoots Sam, then himself. The psychological detail of Joel’s trauma is absent from the game. His emotional vulnerability is meant to parallel the internal struggle he’ll face when deciding whether to save Ellie or let her be euthanized in the attempt to find a cure. But in the game, Joel’s lack of remorse is the point: He’s a man shaped by grief who clings to a second chance to save his daughter. His story isn’t depicted as a redemption arc. His decision to save Ellie isn’t driven by new traumas or softened by emotional fragility. It’s a brutal, morally complex act that left players debating his actions for years.

By layering in this extra context — the grief, the panic, the fatherly sorrow — the showrunners push audiences to empathize with Joel’s decisions. Joel is a broken man after his daughter dies, and he becomes obsessed with saving Ellie because he couldn’t save Sarah. But the show dulls the original narrative’s challenging dilemma about his choices over Ellie. Instead of leaving viewers unsettled by Joel’s capacity for violence, the way the game does — by having him kill dozens of people who are simply trying to develop a cure —the show guides us toward justifying his actions by framing them through a series of emotional parallels.

By the time Joel makes his choice, we’ve been conditioned to empathize with his dilemma. Even the season’s most praised addition, the expanded backstory about the relationship between Bill and Frank (Nick Offerman and Murray Bartlett), is ultimately meant to mirror Joel’s final decision about whether to selfishly save Ellie or let her die for the greater good.

The original The Last of Us game is rich with quiet, intimate moments between Joel and Ellie, small beats that slowly and organically build their bond. The show, however, often sidelines these in favor of expanding peripheral characters like Ellie’s mother Anna (who doesn’t appear in the game), Anna’s friend Marlene, who promised she’d find a cure through Ellie (despite Joel killing her in the season 1 finale), and the loss-stricken Kathleen Coghlan, an original character who mirrors Tess’ revenge story, which was ultimately cut from the original game because the developers didn’t find her cross-state vendetta against Joel realistic.

These additions are primarily meant to underscore thematic parallels with Joel’s decision to save Ellie, but the execution feels heavy-handed, and the dynamic between the protagonists is no longer at the forefront of the story. The show restructures or rewrites original scenes to telegraph themes of loss and sacrifice more explicitly, stripping away the ambiguity that made Joel’s final choice so morally complex. Instead of letting the audience wrestle with the ethics of his actions, the show nudges them toward sympathy.

Season 2 continues this pattern with Ellie, softening her portrayal by dialing down her violent tendencies in favor of a more overtly sympathetic depiction. The season focuses more on the effects of parenthood than on Ellie’s quest for revenge against Joel’s killer. It’s as if Mazin and Druckmann are actively sanding off the rougher, more challenging edges of the games’ narrative, perhaps in an attempt to avoid the backlash and misreadings that followed The Last of Us Part 2. But in doing so, they risk diminishing what made the story resonate in the first place: its refusal to offer easy answers.

Ultimately, the backlash to The Last of Us season 2 isn’t just about controversial plot points or representation — it’s about the culmination of narrative choices that have gradually chipped away at what made the original story so powerful. By softening Joel’s brutality, sanding down Ellie’s rough edges, and over-explaining themes that once thrived in moral gray areas, the adaptation trades nuance for clarity and catharsis for comfort. These aren’t new problems: They were seeded in season 1. Season 2 simply made them impossible to ignore.

Source:https://www.polygon.com/entertainment/603718/last-of-us-season-2-criticism-backlash